Witchcraft in Europe

I thought it would be good to start with a proper clarification of what we're talking about. Some of the history we're discussing can actually be seen stemming from accusations made against Christians by Romans, by early Christians against heretics (dissenters from the core Christianity of the period) and Jews, by later Christians against witches, and, as late as the 20th century, by Protestants against Catholics. It includes accusations of child sacrifice, blood drinking, communing with devils, and so on.

But what makes western witchcraft accusations unique is how, by the 14th century, a deep seated fear of heresy and of Satan added in charges of diabolism to usual indictments of witches, maleificum (malevolent sorcerers), and the like. Starting around the 1300s and all the way up through the late 1700s, witchcraft was viewed as a combination of sorcery, devil worship, the selling of one's soul to Satan, and desecration of the crucifix. And it also includes the belief that witches rode through the air at night to "sabbats" (or secret meetings), where all manner of depravity took place. Sexual orgies, having sex with demons or Satan himself, shapeshifting, conjuring familiars, kidnapping, murdering, and eating of children, rendering their fat for potions.

Episode: File 0048: Witch Please Pt.1

Release Date: October 22 2021

Researched and presented by Halli

These fears became so bad amongst the general populace in Europe that witches, witch hunting, and definitions of witches and sorcery were inscribed into law. Actual law by which government officials, priests, and judges could use to charge, try, and punish so-called witches. This belief was incredibly strong; it seems pretty ludicrous today but then again, we have people who think Democrats are sacrificing children in the back of pizza parlors. And then there's the Satanic Panic of the 1980s in the US and Canada

Step 1: Identify the Witch

So how could you get accused of being a witch in Europe during this time? It really didn't take much.

Charges of maleficium were prompted by a wide array of suspicions. It might have been as simple as one person blaming his misfortune on another. For example, if something bad happened to John that could not be readily explained, and if John felt that Richard disliked him, John may have suspected Richard of harming him by occult means. The most common suspicions concerned livestock, crops, storms, disease, property and inheritance, sexual dysfunction or rivalry, family feuds, marital discord, stepparents, sibling rivalries, and local politics. Maleficium was a threat not only to individuals but also to public order.

So you have people accusing each other, and then you have religion playing a huge role in this and many other accusations. Most of this stems from how the church launched theological and legal attacks on those they deemed heretical. Heresy is a fully religious term, even though we may use it more casually today.

In Christianity, the church from the start regarded itself as the custodian of a divinely imparted revelation which it alone was authorized to expound under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Thus, any interpretation that differed from the official one was necessarily "heretical" in the new, pejorative sense of the word.

Accusations similar to those expressed by the ancient Syrians and early Christians appeared again in the Middle Ages. In France in 1022 a group of heretics in Orléans was accused of orgy, infanticide, invocations of demons, and use of the dead children's ashes in a blasphemous parody of the Eucharist. These allegations would have important implications for the future because they were part of a broader pattern of hostility toward and persecution of marginalized groups.

That pattern took shape in 1050-1300, which was also an era of enormous reform and focus in both the ecclesiastical and secular aspects of society, an important aspect of which was suppressing dissent. The visible role played by women in some heresies during this period may have contributed to the stereotype of the witch as female. (We'll talk later about if witch hunts in Europe were attempts at gendericide and the like.) But ultimately, it was a deep terror of Satan that kept the populace in line and fueled accusations of witchcraft and witchery across Europe.

Western Germany, the Low Countries, northern Italy, and Switzerland were all areas where prosecutions for heresy had been plentiful and charges of diabolism were prominent. In Spain, Portugal, and southern Italy, witch prosecutions seldom occurred, and executions were very rare. We'll touch on most of these, but England is something we'll talk about later; I want to focus there because what occurred in England fueled what happened in the States.

It's been nearly impossible to say when the first witch trial in medieval Europe occurred. Even though the clergy and judges in the Middle Ages were skeptical of accusations of witchcraft, the period 1300-30 can be seen as the beginning of witch trials. In 1374 Pope Gregory XI declared that all magic was done with the aid of demons and thus was open to prosecution for heresy.

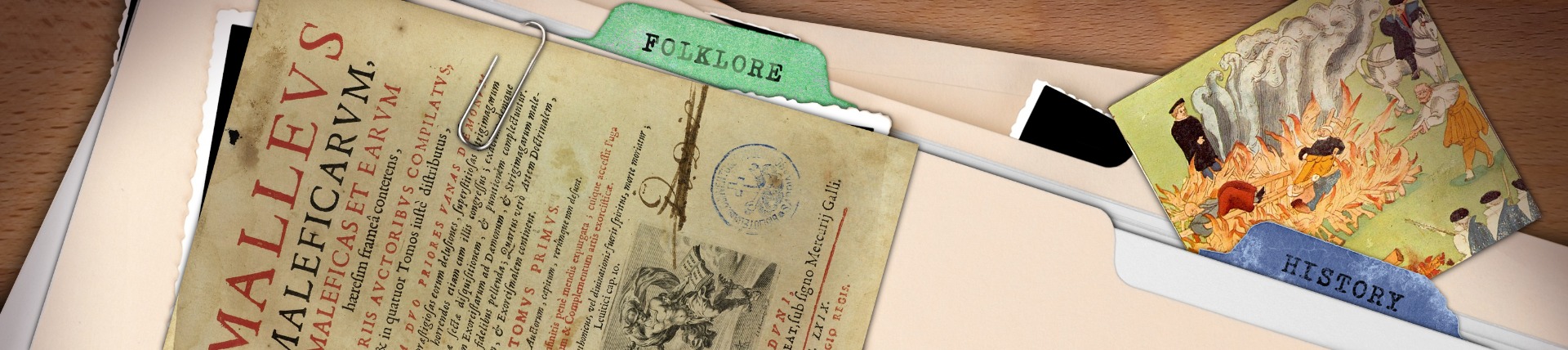

Witch trials continued through the 14th and early 15th centuries, but records are either hard to find or deeply inconsistent. By the mid 1430s, the number of prosecutions had begun to rise and toward the end of the 15th century, two events really kicked off the rabid desire to hunt for witches: Pope Innocent VIII's publication in 1484 of the bull Summis desiderantes affectibus ("Desiring with the Greatest Ardour") condemning witchcraft as Satanism, and the publication in 1486 of Heinrich Krämer and Jacob Sprenger's Malleus maleficarum ("The Hammer of Witches"), a deeply misogynist book blaming witchcraft chiefly on women. Keep the Malleus Maleficarum in your mind cause we're going to look at that book in particular and how it influenced a man named Matthew Hopkins.

The hunts were most severe from 1580 to 1630, and the last known execution for witchcraft was in Switzerland in 1782. Best guess is that 110,000 people in all were tried for witchcraft, and anywhere from 40,000 to 60,000 executed.

Another clarification: The "hunts" were not pursuits of individuals already identified as witches but efforts to identify those who were witches. The process began with suspicions and, occasionally, continued through rumours and accusations to convictions. The overwhelming majority of processes, however, went no farther than the rumour stage, for actually accusing someone of witchcraft was a dangerous and expensive business. The accusations were usually made by the alleged victims themselves, rather than by priests, lords, judges, or other "elites." Successful prosecution of one witch sometimes led to a local hunt for others, but larger hunts and regional panics were confined (with some exceptions) to the years from the 1590s to 1640s. Very few accusations went beyond the village level.

Malleus Maleficarum

Read from The Enemy Within:

The height of the German witch frenzy was marked by the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum ("Hammer of Witches"), a book that became the handbook for witch hunters and Inquisitors. Written in 1486 by Dominicans Heinricus Institoris and Jacobus Sprenge. Written in Latin, the Malleus was first submitted to the University of Cologne on May 9th, 1487.

The Malleus was used as a judicial case-book for the detection and persecution of witches, specifying rules of evidence and the canonical procedures by which suspected witches were tortured and put to death. Thousands of people (primarily women) were judicially murdered as a result of the procedures described in this book, for no reason than a strange birthmark, living alone, mental illness, cultivation of medicinal herbs, or simply because they were falsely accused (often for financial gain by the accuser). The Malleus serves as a horrible warning about what happens when intolerance takes over a society.

Although the Malleus is manifestly a document which displays the cruelty, barbarism, and ignorance of the Inquisition, it has also been interpreted as evidence of a wide-spread subterranean pagan tradition which worshiped a pre-Christian horned deity, particularly by Margaret Murray.

Murray is a fascinating figure. Margaret Alice Murray (13 July 1863 - 13 November 1963) was an Anglo-Indian Egyptologist, archaeologist, anthropologist, historian, and folklorist. The first woman to be appointed as a lecturer in archaeology in the United Kingdom, she worked at University College London (UCL) from 1898 to 1935. She served as President of the Folklore Society from 1953 to 1955, and published widely over the course of her career.

Murray's interest in folklore led her to develop an interest in the witch trials of Early Modern Europe. In 1917, she published a paper in Folklore, the journal of the Folklore Society, in which she first articulated her version of the witch-cult theory, arguing that the witches persecuted in European history were actually followers of "a definite religion with beliefs, ritual, and organization as highly developed as that of any cult in the end"

She followed this up with papers on the subject in the journals Man and the Scottish Historical Review. She articulated these views more fully in her 1921 book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, published by Oxford University Press

As a result of her work in this area, she was invited to provide the entry on "witchcraft" for the fourteenth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1929. She used the opportunity to propagate her own witch-cult theory, failing to mention the alternate theories proposed by other academics. Her entry would be included in the encyclopedia until 1969, becoming readily accessible to the public, and it was for this reason that her ideas on the subject had such a significant impact. It received a particularly enthusiastic reception by occultists.

Murray reiterated her witch-cult theory in her 1933 book, The God of the Witches, which was aimed at a wider, non-academic audience. In this book, she cut out or toned down what she saw as the more unpleasant aspects of the witch-cult, such as animal and child sacrifice, and began describing the religion in more positive terms as "the Old Religion".

In The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, Murray stated that she had restricted her research to Great Britain, although made some recourse to sources from France, Flanders, and New England. She drew a division between what she termed "Operative Witchcraft", which referred to the performance of charms and spells with any purpose, and "Ritual Witchcraft", by which she meant "the ancient religion of Western Europe", a fertility-based faith that she also termed "the Dianic cult". She claimed that the cult had "very probably" once been devoted to the worship of both a male deity and a "Mother Goddess" but that "at the time when the cult is recorded the worship of the male deity appears to have superseded that of the female".

Describing this witch-cult as "a joyous religion", she asserted that the "General Meeting of all members of the religion" were known as Sabbaths, while the more private ritual meetings were known as Esbats. The Esbats, Murray claimed, were nocturnal rites that began at midnight and were "primarily for business, whereas the Sabbath was purely religious".

A big controversial aspect of her thesis was her assertion that there were covens of witches very highly placed in the court of James VI, who tried to use magic and poison to assassinate the King; and advance the cause of their leader, Francis Stewart, the Earl of Bothwell, who was a successor to the throne of Scotland, and potentially of England. Murray also hypothesized that Joan of Arc and her companion Giles de Rais were avatars of the witch god, ritually assassinated at the end of their reigns.

Murray's interpretation of history is not provable by the strict standards of the historian. She was highly selective about which historical evidence she utilized, which left her open for criticism by the academic establishment.

Murray also proposed that Fairies (and Elves, Dwarves, Brownies, etc.) were an actual subculture of (full-sized, if slightly stunted by their diet) human beings who lived secretively in the British Isles, persecuted along with the witches. She speculated that the Fairies were a survival of a pastoralist neolithic culture. This culture survived, like the Romany (Gypsy) people, on the periphery, avoiding contact with the dominant culture. The fairy hills of legend were descriptions of their underground residences. They were later converted into the 'wee folk' of legend by Shakespeare, and the folklorists. One interesting aspect of her hypothesis about Fairies is that they appeared to have a matriarchial culture. She presents incidental documentary evidence for the existence of a subterranean fairy race, but to my knowledge there is no actual material evidence. I am unaware of any other scholar, either in academia or Wiccan circles, who wholeheartedly endorses this hypothesis about the Fairies.

As for levitation, Murray noted that the witches used herbal ungents which contained known hallucinogens before 'flying', which would have produced ecstatic effects. In addition, the description of the witches' ceremonials included prolonged dancing. It is now known that Shamans used similar techniques, resulting in altered mental states including the sensation of flying. This portion of the hypothesis has been corroborated by other scholars.

As Margot Adler has pointed out in her contemporary book, Drawing Down the Moon, it may be Murray's age in addition to her role as an outspoken academic iconoclast which has caused her ideas to be treated with disdain to the present day. Murray was in her sixties when 'Witch Cult' was published. It might reasonably be argued that her gender has caused academia to ignore her as well.

So basically her theory is that one or several pre-Christian pagan religions were operating underground/in secret and Christians either witnessed this worship or a symbol of the deity, assumed it was the devil, and this is how tens of thousands of people were executed

Murray's witch-cult theories provided the blueprint for the contemporary Pagan religion of Wicca, with Murray being referred to as the "Grandmother of Wicca". Wicca's theological structure, revolving around a Horned God and Mother Goddess, was adopted from Murray's ideas about the ancient witch-cult, and Wiccan groups were named covens and their meetings termed esbats, both words that Murray had popularized. As with Murray's witch-cult, Wicca's practitioners entered via an initiation ceremony; Murray's claims that witches wrote down their spells in a book may have been an influence on Wicca's Book of Shadows. Wicca's early system of seasonal festivities were also based on Murray's framework.

The main purpose of the Malleus was to refute claims that witchcraft did not exist, to refute those who expressed skepticism about its reality, to prove that witches were more often women than men, and to educate magistrates on the procedures that could find them out and convict them. The main body of the Malleus text is divided into three parts; part one demonstrates the theoretical reality of sorcery; part two is divided into two distinct sections, or "questions," which detail the practice of sorcery and its cures; part three describes the legal procedure to be used in the prosecution of witches. The Malleus was republished 26 times in the Early Modern period and remained a standard text on witchcraft for centuries.

The relatively few prosecutions of witches in Spain, Italy, and France, for example, can be attributed to the fact that neither the Spanish nor the Roman inquisition believed that witchcraft could be proven. England likewise saw relatively few prosecutions due to the checks and balances inherent in the jury system. It was only in places like Scotland, the Alpine lands, and in South German ecclesiastical principalities that witch panics and actual prosecutions proliferated. Another important reason for the active conviction of witches in the German states was the Holy Roman Empire's adoption of the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina in 1530, which not only instituted prosecution at the judge's initiative, thus putting the accused witches at the mercy of a magistrate who was at once judge, investigator, prosecutor, and defense counsel, but also provided for the secret interrogation of the accused, denied him or her counsel, required torture in order to extract a confession, and specified that witches be punished with death by burning.

Gendericide?

Matthew Hopkins, Witchfinder General

Matthew Hopkins (c. 1620 - 12 August 1647) was an English witch-hunter whose career flourished during the English Civil War. He claimed to hold the office of Witchfinder General, although that title was never bestowed by Parliament. His activities mainly took place in East Angliaa

Hopkins' witch-finding career began in March 1644 and lasted until his retirement in 1647. He and his associates were responsible for more people being hanged for witchcraft than in the previous 100 years, and were solely responsible for the increase in witch trials during those years. He is believed to have been responsible for the executions of over 100 alleged witches between the years 1644 and 1646.

It has been estimated that all of the English witch trials between the early 15th and late 18th centuries resulted in fewer than 500 executions for witchcraft. Therefore, presuming the number executed as a result of investigations by Hopkins and his colleague John Stearne is at the lower end of the estimates, their efforts accounted for about 20% of the total. In the 14 months of their crusade Hopkins and Stearne sent to the gallows more accused people than all the other witch-hunters in England of the previous 160 years.

Little is known of Matthew Hopkins before 1644, and there are no surviving contemporary documents concerning him or his family. He was born in Great Wenham, Suffolk and was the fourth son of six children. His father, James Hopkins, was a Puritan clergyman and vicar of St John's of Great Wenham, in Suffolk. The family at one point held title "to lands and tenements in Framlingham 'at the castle'". His father was popular with his parishioners, one of whom in 1619 left money to purchase Bibles for his then three children James, John and Thomas.

Thus Matthew Hopkins could not have been born before 1619, and could not have been older than 28 when he died, but he may have been as young as 25.

In the early 1640s, Hopkins moved to Manningtree, Essex, a town on the River Stour, about 10 miles (16 km) from Wenham. According to tradition, Hopkins used his recently acquired inheritance of a hundred marks to establish himself as a gentleman and to buy the Thorn Inn in Mistley. From the way that he presented evidence in trials, Hopkins is commonly thought to have been trained as a lawyer, but there is scant evidence to suggest this was the case.

The witch-hunts undertaken by Stearne and Hopkins mainly took place in East Anglia, in the counties of Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire, with a few in the counties of Northamptonshire and Bedfordshire. They extended throughout the area of strongest Puritan and Parliamentarian influences which formed the powerful and influential Eastern Association from 1644 to 1647, which was centered on Essex. Both Hopkins and Stearne would have required some form of letters of safe conduct to be able to travel throughout the counties.

It's important to note that he worked without any real authority - his role of 'witchfinder' was, in essence, as a freelance finder 'evidence', which was then used as the means for trials to go ahead.

He first appears in records around 1644 when an associate, John Stearne, accused a group of women in Manningtree, Essex, of trying to kill him with sorcery. Hopkins enthusiastically joined in with the 'investigations', that involved subjecting the accused to sleep deprivation and searches of their bodies by women known as 'searchers' or 'seekers', looking for a physical deformity or blemish which could be called a 'Devil's Mark'.

Thirty-six local women were eventually charged with witchcraft, their names given either under 'confession' or by townsfolk accusing others. Following a trial overseen by the Earl of Warwick, 19 of these women were hanged in July 1645.

The next month, the largest witch trial in English history was held at Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk where 18 people - 16 women and two men - were hanged on evidence supplied by Hopkins and Stearne. Around a hundred more accused lingered in filthy conditions in prison, with some undoubtedly succumbing to disease and the elements.

Together with their female assistants, they were well paid for their work, and it has been suggested that this was a motivation for his actions. Hopkins states that "his fees were to maintain his company with three horses", and that he took "twenty shillings a town". The records at Stowmarket show their costs to the town to have been £23 (£3,800 as of 2021) plus his travelling expenses.

The cost to the local community of Hopkins and his company were such that, in 1645, a special local tax rate had to be levied in Ipswich. Parliament was well aware of Hopkins and his team's activities, as shown by the concerned reports of the Bury St Edmunds witch trials of 1645. Before the trial, a report was carried to the Parliament - "as if some busie men had made use of some ill Arts to extort such confession" - that a special Commission of Oyer and Terminer was granted for the trial of these witches. After the trial and execution the Moderate Intelligencer, a parliamentary paper published during the English Civil War, in an editorial on September 1645 expressed unease with the affairs in Bury.

Methods of investigating witchcraft heavily drew inspiration from the Daemonologie of King James, which was directly cited in Hopkins' The Discovery of Witches. Although torture was nominally unlawful in England, Hopkins often used techniques such as sleep deprivation to extract confessions from his victims. He would also cut the arm of the accused with a blunt knife, and if she did not bleed, she was said to be a witch. Another of his methods was the swimming test, based on the idea that as witches had renounced their baptism, water would reject them. Suspects were tied to a chair and thrown into water: all those who "swam" (floated) were considered to be witches. Hopkins was warned against the use of "swimming" without receiving the victim's permission first. This led to the legal abandonment of the test by the end of 1645.

Despite most of it being technically illegal, Hopkins and Stearne used a number of 'tests' - essentially torture - to ascertain whether a woman was a witch, all based on contemporary superstition. This involved 'walking' a woman to exhaustion before questioning, making the accused stand or sit in a room without food or water and 'watching' them for hours.

Hopkins and his company ran into opposition very soon after the start of their work, but one of his main antagonists was John Gaule, vicar of Great Staughton in Huntingdonshire. Various sources claim that between 200 and 300 people were executed as the result of Hopkins and Stearne's activities but they stopped when attention began to mount regarding their motivations, expertise, and authority. The Puritan cleric John Gaule clashed with, and preached against, Hopkins and his book, Select Cases of Conscience touching Witches and Witchcraft, exposed the self-appointed witch-finder's methods. Gaule's campaign worked and in 1647, at the postponed Norfolk Assizes, a group of gentlemen influenced by his writings produced a series of probing question for Hopkins which claimed he used "unlawfull courses of torture to make them say any thing for ease and quiet?" that was "an abominable, inhumane and unmercifull tryall of those poore creatures, by tying them, and heaving them into the water; a tryall not allowable by Law or conscience".

Hopkins retired to Manningtree, where he wrote the self-justifying book, A Discovery of Witches, which tried to rebuff Gaule by detailing his methods and recounting his hunts. Aided by the explosion in demand for the printed word, the book became a minor sensation and not only helped lead to his enduring reputation but undoubtedly influenced the Salem Witch Trials that occurred decades later in Massachusetts. By and large, the jig was up - the political climate was changing as the nature of the Civil War changed and witch trials became fewer in number (though there were further persecutions yet to come later in the century). Hopkins, too, was fading - he died a young man in 1647, most probably from tuberculosis. He was buried in the village churchyard of Mistley Heath in which is now an unmarked grave. A legend that he was swum and hanged as a witch himself was false, even if it would have been a fitting end.

The East Anglia trials of the 1640s remain one of the most evocative 'witch scares' from history, and Hopkins has come to embody this brief moment of hysteria, zealotry, and unreason. But how do we explain his sudden rise and equally sudden fall? In Witchfinders: A Seventeenth Century Tragedy, Malcolm Gaskill suggests that witch-hunts in the early modern period acted as a kind of 'pressure valve' during moments of tension within communities created by warfare or economic stress. By successfully finding 'witches' in their midst, Hopkins allowed these communities to 'release' the emotional pressure they felt by focusing on an individual or group that was perceived as 'different' or 'troublesome'. While the pressures on communities did not ease as the English Civil Wars progressed through the 1640s, the way they confronted and expressed their stress did. This, combined with greater resistance from the structures of state to such unrest and an increase in condemnation from the pulpit, meant that the power of people like Hopkins faded too.

During the year following the publication of Hopkins' book (A Discovery of Witches), trials and executions for witchcraft began in the New England colonies with the hanging of Alse Young of Windsor, Connecticut on May 26, 1647, followed by the conviction of Margaret Jones. As described in the journal of Governor John Winthrop, the evidence assembled against Margaret Jones was gathered by the use of Hopkins' techniques of "searching" and "watching"