Jacob Gray

In 2020, 543,018 missing people were reported in the US. In recent memory these reports peaked in 1996 with 980,712. Reports have been steadily dropping since the late 1990s. A fair number of these reports made are for young people under age 21. It's estimated that between 89 and 92% of people reported missing are soon found.

But what about the ones who aren't found?

Episode: File 0025: Gone But Not Forgotten pt. 2

Release Date: May 7th 2021

Researched and presented by Halli

I first ran across the story of Jacob Gray in the book The Cold Vanish: Seeking the Missing in North America's Wildlands by Jon Billman. It was a book I picked up on a lark and wound up tearing through. He focuses on the case of Jacob Gray, a deep dive into Jacob's life, disappearance, and family (including going with Jacob's father as he searches for his son). It's a stunning read, one I highly recommend. But interwoven in Jacob's story are the stories of others who have gone missing from remote places in North America; how they've disappeared with no or few traces, and how most have never been found. Not even a body for their families to put to rest.

Now to be transparent, Jacob was eventually found. His remains were found in August 2018, about 16 months after he disappeared in April 2017. But it's a bizarre story, one with clues that have never added up and it has left quite a few loose ends.

Jacob Gray

Jacob Gray, 22, originally from Santa Cruz in California, left Port Townsend alone on his bicycle on April 5, 2017, towing a trailer full of camping gear. He planned to travel to the Daniel J. Evans Wilderness in Olympic National Park in Washington before heading east. He was young, healthy, and loved the outdoors.

According to an article in Bicycling (written by Jon Billman, the author of THE COLD VANISH), among his gear was: a secondhand yellow-and-red Burley child trailer with pots, pans, wool blankets, a roll of duct tape, a toolbox, stove, deck of cards, a Holman Bible, a tent, fuel bottles, a case of Mountain House dehydrated meals, two first-aid kits, carabiners, climbing crampons, a bow and quiver of arrows, a rain poncho, sleeping bag, and enough tarps, rope and bungee cords for a one-ring circus. The bike, trailer, and supplies weighed more than the 145-pound 22-year-old did soaking wet.

The bike was not built for speed, not pretty, but it was tight and as utilitarian as a pickup truck.

Jacob, a good surfer who grew up on the beach in Santa Cruz, California, didn't even mind the rain pouring down in this part of the PNW. He loved water, whether surfing on it or riding in it, his father Randy says.

"Even if we don't go surfing, we'll get a mocha and go down to the beach and watch the sunrise. That's our thing, Jacob and me."

He didn't tell anyone where he was going, not even Wyoma Clair, his grandmother, with whom he'd been living in Port Townsend. He just lit out into the headwind and rain sometime in the night of April 4, 2017.

On April 6, 2017, a woman passed Jacob:

"as he churned up the Sol Duc Hot Springs Road, about 2 miles from the 101 (Source). Later that afternoon, she noticed the rig on the side of the road 6.3 miles up-river from the 101; she was curious enough to snap a quick photo of the abandoned contraption, a flash or red and yellow against the green of the forest. The bike Jacob was riding was noticed by Rangers and had remained untouched for most of April 6, 2017 still within sight of pavement, just 40 feet East of the Sol Duc (Quileute Indian for "sparkling waters") River off Milepost 6.3 of Sol Duc Hot Springs Road, in brush. Another ranger recalled having seen the bike and gear, but just figured the rider was on a short excursion on foot. No one gave it much thought. Touring cyclists are common in the area and Jacob was just the first robin of spring.

Rangers became curious as to why the bike (and other equipment/supplies near it) had been abandoned; an order was given by Ranger John Bowie for his fellow Officer, Brian Wray, to follow-up on the situation the following morning. At this time, no missing person report had been filed and a preliminary (unofficial) search of the surrounding area was conducted yielding no answered as to the whereabouts of Jacob Gray.

Several things struck the Rangers as odd:

- It wasn't a good place to camp or stash a bike for long

- it was highly visible not ten yards from the road, twenty from the river.

- It appeared that someone had been organizing gear because a poly tarp was spread out surrounded by camping equipment. Was Jacob wet, cold, tired, and hungry?

- He was 80 miles from his grandmother's house was he miserable and discouraged?

- Or was he totally in his element, feeling the highs of discovering a new independence?

- Oddly, there were four arrows stuck in the ground in an east-west line near the tarp. Why were they stuck in the ground?

- Was it some sort of sign for people who would come upon the bike?

A person isn't missing until they're reported missing. Even then, going missing isn't a crime or even an emergency if the missing person is over 18. In this case, no one reported Jacob missing at all. Unlike hikers and runners, vanished cyclists are rare. But the fact that the bike remained untouched for most of a day made rangers curious.

The following day, April 7, a follow-up was conducted on the area; Ranger Wray noted no alteration from the original position/location/state of Jacob Gray's belongings. A check of the Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort (located in Port Angeles, Washington) answered no questions, as no one reported seeing the cyclist in the area. Seeing as there was no sign of Jacob Gray in/near the Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort, and the fact that his belongings off Milepost 6.3 of Sol Duc Hot Springs Road were in full working order, ideas began to circulate that the cyclist must have fallen into the 40-degree river; a report released the following quote,

"we'll check the river in the summer when the water goes down."

They didn't have much to go on, other than an abandoned bicycle. Jacob's bike and trailer were functional-the tires were not flat, there was no evidence he'd been hit by an automobile. Nothing appeared malfeasant-most of his gear was there, and he probably had his wallet in his pocket.

Information was eventually recovered from the initial location and led to the identification of Jacob Gray. Among Gray's belongings was a list of phone numbers, one of those numbers belonged to his sister, Mallory. When Ranger Wray called Mallory, she asked the Ranger to inform their parents immediately. From the list of items Jacob was suspected to have left with, Rangers were able to identify that the belongings matched the general description and noted only two items missing from that list: a water filter and Camelback backpack (which holds a plastic water container).

Rangers photographed the bike, trailer and gear, then loaded everything up and locked it in a boathouse on Lake Crescent, where they took a detailed inventory. Randy, Jacob's dad, dropped his hammer gun (he builds houses for a living) and threw his wetsuit into his truck. Rangers told him the bike was found near the river and Randy had a sense he'd be searching swift water. He picked up Mallory, Jacob's sister, and sped north, driving the thousand miles from Santa Cruz straight-through.

"I drove all night," Randy said. "I got stopped going a hundred miles an hour in Oregon. I told him what was going on. He said, I'm not the last cop to not give you a ticket. Just be careful."

It was already Tuesday by the time Randy and Mallory got to the scene, five days after rangers were first puzzled by the lonely bike. Other family members-including Laura, Jacob's mom-and friends flew into SeaTac and drove to the park, an unfortunate occasion for a reunion.

Randy and Mallory arrived at the park on Tuesday, April 11. Laura and Dani Campbell, 36, a cousin and experienced surfer who worked construction for Randi and helped renovate the Gray family home, met them-Randy and Dani suited up and got into the river. The family sensed lethargy with park officials and decided to shake the tree themselves. Elise Stokes, Jacob's aunt who lives in Bellevue, Washington, told Ranger Wray:

"We as Jacob Gray's family demand an intense search."

She was told by Wray, Ok.

When Randy wasn't in the water searching behind falls and in deep holes and under logjams, he bushwhacked through thick brush and thorny Devil's club in the rain. Randy didn't have proper terrestrial gear, and wore cotton under his PVC rain suit, so that by nightfall he was just as soaked on the inside as on the outside. He suffered trench foot from wet socks. But he never complained. And the longer he searched and didn't find Jacob in the probable places, the better, he hoped, the chances his son was still alive.

On April 12, another search was conducted by volunteers in the area where Gray's bike was found. Evidence was recovered that led to the idea that someone had swapped hiking boots for running shoes, and discovery of a mark on a mossy rock led searchers to theorize that someone had fallen into the river. Signs of an attempt to leave the water was discovered about 90 feet (about 30 yards) downstream; a state Fisheries Biologist was assigned to search two log jams following these findings. The following day, around 5:00pm, dog teams were deployed; two cadaver dogs hit on a log jam. According to The Guardian,

"[cadaver] dogs are trained to smell decomposition, which means they can locate body parts, tissue, blood and bone. They can also detect residue scents, meaning they can tell if a body has been in a place, even if it's not there anymore."

After all log jams were searched - some 12 miles either side from where Gray's bike was located - no body was recovered.

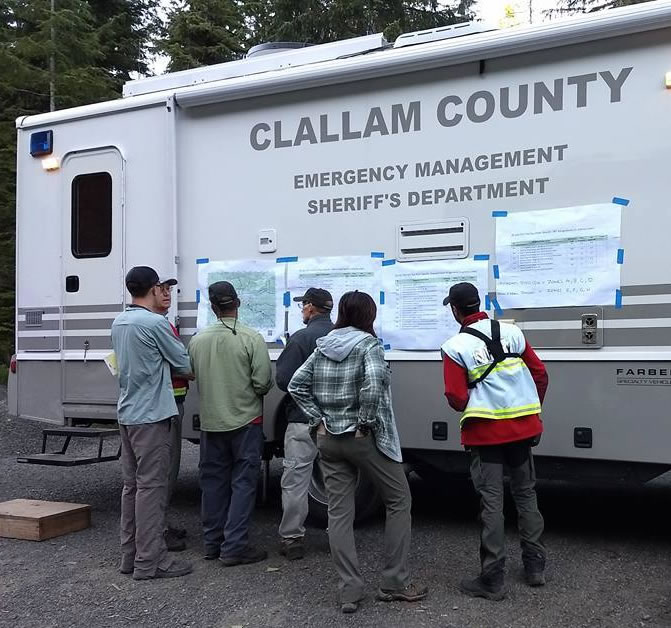

Another search on the west side of the river, on Olympic National Forest land, and inside the Olympic National Park was conducted on April 15, 2017 was conducted by the Clallam County Search-and-Rescue with the help of volunteers. A pair of Burnside shorts, in Jacob's size, were recovered a few miles downstream. This evidence was sent off for DNA testing in Seattle, Washington.

On April 16, 2017, the search was scaled back. Neither the Coast Guard nor aircraft from Whidbey Island Naval Air Station had been called to assist in search efforts; the Park reportedly declined the family's team of volunteer searchers.

Randy's search

From where the bike was found, the Sol Duc runs 78 miles to the Pacific Ocean. Swiftwater rescue experts will tell you that if he fell or jumped into the water, it's nearly impossible that he went that far, and it's improbable he'd flow more than a mile. It's likely Jacob could be wearing a wool coat and canvas Carhartt dungarees. This is not an outfit you want to fall into a river wearing, but Jacob was as strong a swimmer as they come. In the water he knew when to relax and go with the current, and when to stroke like hell. There were logjams not far downstream from the bike, where he might have landed and paddled his way ashore. A person who falls into a cold river and inhales water will sink. A body-limbs and fingertips-can be caught by strainers in the river easier than you'd think, so it's not likely he'd travel very far downstream. Eventually in cold water-three weeks, a month or so-decomposition produces gases that will cause the body to bloat and often float to the surface.

"I didn't cuss before this," Randy told me. "Now I curse all the time. I'm thinking, Where the hell is my boy."

Randy went back to Santa Cruz after the initial passive search ended, to begin closing up his successful contracting business. He would then, until fall, commute back and forth, searching the river and possible, improbable, routes higher on the mountain. Randy-as well as Laura and Peninsula friends-spent hundreds of hours hiking through snow and brush. But his search would broaden to include other possibilities.

By the summer of 2017, Randy was essentially living on the Olympic Peninsula, still searching. He believed Jacob was still alive, on some sort of quest, and he was determined to find him. Randy sold the family home in Santa Cruz, bought a diesel Dodge dually pickup and a slide-in camper. He picked up a Cayne folding mountain bike with 20-inch knobby tires at Port Townsend Cyclery-and kept it in the truck. The small red 3-speed was handy to take on ferries when he hunted for Jacob on the San Juan Island chain. There are a dozen organic farms out there, maybe Jacob was working on one, laying low.

Randy Gray, Jacob's father, dedicated his financial resources toward the search for his son, sometimes living off River water, searching caves along waterways and even extended his search to other areas of the Country and into Canada. A team of Bigfoot researchers called the "Olympic Project," welcomed Randy in and assisted with an official search of the surrounding area where Jacob would possibly be found. The Olympic Project would soon create the "Olympic Mountain Response Team," an offshoot devoted to "responding to missing persons in the mountains."

No 12-mile stretch of mountain river had been searched more thoroughly. There's a large waterfall just upriver, Salmon Falls. One day, Randy pulled on his Santa Cruz-weight wetsuit, tied himself to a rope and knotted it off to a Sitka spruce tree. He lowered his mask and grabbed a boulder-so he could sink to the bottom-and leapt from a cliff into the pool behind the falls. Not long after Jacob vanished, Randy wore his wetsuit, snorkel and diving mask, and literally boogie-boarded the North Fork of the Sol Duc, stopping to search pools and caves. The North Fork was another unlikely place for Jacob to be, but by then most places were unlikely. Randy didn't eat much, he drank only river water, his body was bruised all over from bashing into boulders. The search for his son nearly killed him. Living on the open road in a self-contained camper, changing parks, forests and beaches on a whim-that's every rich man's dream. But for Randy Gray, it was a nightmare. He lost his kid.

"I didn't plan any of this," Randy said. "Jacob's my buddy. You think I want to be out here searching for my son?" We were resting on a massive Western hemlock log, but not long. Randy prefers moving, because if he stops he'll start thinking too much. "That's the thing-you think you know, but you don't: Where Jacob was going. What he was thinking. Where he is now." It's like surfing, you have to be fluid and reflexive-if you overthink, you're in trouble.

Finding Jacob

"They found Jacob," Randy said while he was driving north, again, from Santa Cruz to the Olympic Peninsula on Sunday, August 11, 2018. It had been 16 months since Jacob vanished. In that time Randy had been back and forth, searching throughout the Olympic Peninsula, San Juan Islands, the Gulf Islands of Canada, Northern California, southern British Columbia, Vancouver Island across the Straight of San Juan de Fuca from Olympic National Park, parts of Idaho, most of Oregon and Eastern Washington.

On Friday, August 10, a team of biologists who made a trip into the mountains to study marmots found Jacob's remains, clothing, gear and wallet, near the top of a ridge above Hoh Lake, 5,300 feet above sea level and at least 15 miles from where he left his bike. His body wasn't found near a trail; in April the terrain would have been snowy and prone to avalanches.

Ranger Wray told Randy, "Don't go up there, let us do our job." Wray and Randy had become friends over the months of searching and it's clear that Wray cares about Randy. But, of course, Randy didn't listen.

"What would you do?" Randy said. "When does a dad stop being a dad?"

Randy-who wasn't sure of the exact location when he busted up the mountain solo-missed the rangers who were packing Jacob's remains out. On his way down, above Deer Lake, Randy came across other rangers administering CPR to a 29-year-old woman from Iowa who had suffered cardiac arrest-he stayed and helped the rangers, taking turns with the chest compressions. One of the rangers had been part of the small team who'd just brought Jacob off the mountain. The woman died.

The Clallam County Coroner's office told me the official cause of death is inconclusive-they identified Jacob through dental records. He had a cigarette lighter and insulated clothing and plenty of food with him. He carried another bible-Laura's father's.

The remains were confirmed to be Jacob Gray's on August 18, 2018 by the King County Medical Examiner's Office, but no autopsy could be performed. Katherine Taylor, an Anthropologist for the King County Medical Examiner's Office, indicated that the cause of death could not be determined; Clallam County Assistant Coroner Tellina Sandaine said, "it was most likely from a natural cause," the official cause of death was ruled as "inconclusive."

It's likely Jacob succumbed to hypothermia, but that can be a catch-all for people who perish in the mountains. What led to freezing to death? We'll likely never know.

Days after the remains were found, Randy, Micah and Billman hiked up to the spot where Jacob perished, just to see where it happened. They stumbled upon two human bones, one of them a finger bone, that they believe belonged to Jacob. Rather than bringing it to authorities, they had a burial on the mountain, fashioning a cross of tree limbs tied together with a parachute cord.

Jacob's mental state

The Gray's divorce four years prior had hit Jacob hard. Jacob's mother Laura spoke with Jacob a couple nights before he left Port Townsend. She understood that Jacob was all geared-up for a cross-country tour to Vermont to see his older brother, Micah, who was stationed there with the U.S. Coast Guard. Jacob said he might take two years to make the trip. He figured he could do odd jobs along the way, maybe a little seasonal work as a transient organic farmhand. If that was his plan, then why would he ride west in weather, even if it was just a shakedown ride?

"We live in a really big strange creepy world," Mallory said. For a year, as a teenager, she left home and lived a version of on-the-street, except it was in a tent in the redwoods. She said Jacob was an introverted kid who struggled with the transition to adulthood-envied that move in a way. "Jacob was really lost. He didn't know what he wanted to do in life, where he wanted to go, what he wanted to be. The state of the world had gotten him down. He sought answers in the Bible."

The Holman Bible found with Jacob's things had Isaiah 34:14 circled:

And an abode of ostriches. And the desert creatures shall meet with the wolves, The hairy goat also shall cry to its kind; Yes, the night monster shall settle there.

Jacob once walked from Santa Cruz to San Francisco because he felt like walking. Jacob had called her during the walk and said he was hungry, Mallory told me. She took him some supplies part way there. Considering what was not at his grandmother's house, and not with his gear at the bike, Mallory figures Jacob had everything he needed for a long walk.

"Anything is possible at this point," Mallory said. But she doesn't think self-harm is likely. "Jacob couldn't kill a spider, let alone kill himself."

But his family had been worried that Jacob was showing signs of mental health issues. Randy said Jacob hadn't been himself and cites the divorce and losing the beloved home he grew up in as possible triggers. "He was having trouble adulting," Laura said. A cross-country bike tour seemed like a good remedy, a chance for growth and change.

What could have helped?

Rangers told Laura they had a lot going on in their park. In a place that's 200,000-acres larger than Yosemite and sees almost four-million visitors a year, they're terribly understaffed, with nearly two-thirds of their law-enforcement personnel having been transferred to other parks and not replaced due to 2013 budget cuts. Within a week of Jacob's bike being found, there was also a plane crash and then another missing person in the park. They didn't have the bandwidth to do a full-scale search.

The family was surprised to find that no ranger-assisted search had been launched. National Parks operate like sovereign countries; search and rescue personnel from outside the park must be requested by park officials in order to search. Jacob's bike was found less than 40 feet from the river, which was 40-feet wide at the high water mark. On the other side is the Olympic National Forest, another jurisdiction. Unlike national parks, national forests operate under the county model, and the sheriff of Clallam County, Washington, is in charge of search and rescue there, a stone's throw away. The Coast Guard, based in Port Angeles, was not requested and neither were aircraft from Whidbey Island Naval Air Station, which assists with some Olympic National Park searches.

Where were the dog teams? Dog teams are almost entirely volunteer -Randy and Mallory had lined up a willing team but the park said no, they had another volunteer team in mind (that they were hesitant to request). Olympic National Park, not unlike many large national parks, opted to keep the searching in-house.

Jacob's older brother, Micah, is in the Coast Guard, and when the Coast Guard offered their Port Angeles-based helicopter-a five-minute flight away-they were waved off by park officials. If Jacob had indeed fallen into the river he'd have survived for less than 20 minutes in the sub-40-degree water. If he'd swam to the far bank and scrambled out, he would have quickly come to the Forest Service road used by loggers and recreators. Other than that, there just weren't enough clues in the Park Service's estimation to allocate more resources to Jacob's search. "It's beyond finding a needle in a haystack," Chief Ranger Jay Shields told said. What about the other clues, like the claw marks on the root ball downstream? Shields, a tracker himself, puts the probability that the tracks are Jacob's at less than five percent-myriad things could have made those marks on the bank, an otter, a beaver, a mountain lion.

Jacob's search was termed by the park a "passive search," which essentially means that resources will not be allocated unless new information arises.

Conclusion

After all the time he put into prepping for a bike journey, why would Jacob abandon his bike? And why wouldn't he contact his family-his sister-like he did on the walk to San Francisco? He'd left his phone in Port Townsend.

Why did he plan and tell people he was headed east, then go west without telling anyone? Why was the bike parked where it was, unlocked and in full view of traffic, with gear laid out? Why were four arrows stuck in the ground?

His family wonders if he could have been found alive if officials had gotten a helicopter in the air and dogs into the backcountry within a day or so of finding the abandoned bike? Jacob's remains were found on a treeless ridge and might have been seen from the air.

People go missing in national parks A LOT. Sometimes they're found. Other times, like Jacob Gray, only their bodies are discovered long afterwards.

Sources

- https://www.bicycling.com/culture/a27335681/jacob-gray-disappeared-bike-ride/

- https://www.strangeoutdoors.com/mysterious-stories-blog/jacob-gray

- https://www.peninsuladailynews.com/news/remains-found-in-olympic-national-park-identified-as-missing-hiker/

- https://nypost.com/2020/07/04/why-hundreds-of-people-vanish-into-the-american-wilderness/

- https://missingnpf.com/the-disappearance-of-jacob-gray/

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/240401/number-of-missing-person-files-in-the-us-since-1990/

- https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/cjis-link/fbi-releases-2019-missing-person-statistics