Bicycle Face

"Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammeled womanhood." —Susan B. Anthony in The New York World, February 2, 1896 (Page 42, Column 3)

It started with something called the "penny farthing". Not a coin, despite the name, but rather a bicycle. And no, not like the thing gathering dust in your garage or basement or attic, its handles slowly rusting and the plastic grips disintegrating.

Episode: File 0146: The Ancient Writings of Bicycle Face

Release Date: May 22 2025

Researched and presented by Halli

The Penny Farthing wasn't the first iteration of the bicycle. That honor goes to the "boneshaker", referring to the human-powered machine's incredibly uncomfortable ride due to the stiff wrought-iron frame and wooden wheels surrounded by tires made of iron. The boneshaker came around in the 1860s in France, and it kicked off the first leg of the bicycle craze. There aren't many boneshakers left outside museums, as many were "melted for scrap metal during World War I". There were other velocipedes before the boneshaker, like the "dandy horse" created by German Karl von Drais in 1817. Not all velocipedes had two wheels: from the unicycle to the tricycle, and even the quadricycle, velocipedes have been a part of culture for well over a century and a half.

Velocipedes weren't mass produced until 1857, so they were quite uncommon. And really uncomfortable - metal and wood across cobblestone streets or dirt roads? But by the 1870s, advancements in metallurgy allowed for the first all-metal velocipedes. They were still hard as hell to ride, from the height to the giant front wheel, since manufacturers figured out that the larger the wheel, the further you could travel on one rotation of the pedals (at this time, the pedals were directly attached to the front wheel).

The penny farthings weren't without issue as well. The only shock absorption happened in the saddle, so your rear took all the hits because the tires were solid rubber. A lot of folks referred to these contraptions as bicycles, even with the official name (due to how the penny was much larger than the farthing, and if you looked at a penny farthing cycle from the side, the front wheel was much larger than the back).

Advancements in bicycle science and construction continued through the end of the 1800s. Enthusiasts raced penny farthings and boneshakers, creating the sport of cycling. But up until the mid 1880s, women were dependent on men to take part in cycling. Granted, the boneshaker and penny farthing were quite dangerous to use, as two-seater sociables, the tandem bicycle, and the tricycle were added to the offerings, women were allowed to use these with a friend or spouse. The invention of these "coed" bicycles also created a new type of socialization, even if the man was in charge of the velocipede because it was "assumed that the man could keep the woman safe from the dangers of riding a bike alone".

The bicycle we're all familiar with was invented in the late 1880s and dubbed the "safety bicycle". The rider's feet could touch the ground, unlike the penny farthing and boneshaker. Usually the wheels were the same size (I say usually because that wasn't always the case!). Immediately, inventors started adding new mechanisms, including a chain drive (1879), multiple gears (1885).

I did find it very interesting that there was great opposition to cycling in the Ottoman Empire, with conservatives and religious fundamentalists calling bicycles the "Devil's Chariot". Also, "Orthodox scholars claimed that cycling would harm reproductive organs, embolden sexual permissiveness and lead to the destruction of the family". Obviously the goal is to keep women at home where they weren't with men outside family or marriage, unsupervised.

And this makes for a great transition into bicycle face and why the bicycle was a symbol and mechanism for feminism.

By the time women were riding tricycles around town, the bicycle had become both a mainstay and part of a grassroots effort in the later 1800s. In the US, after the Civil War, people were using the bicycle to create leisure time, and get out of the city and into the country. Bicycling as a sport was all the rage, but it only accepted men, and women's clothing really didn't allow them to ride the popular two-wheel contraptions men scooted around town on.

"The high-wheel bicycle became a man's bicycle because of cultural perceptions," Roger White, curator in the Division of Work and Industry at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History, says. Roads weren't smooth or paved in those days, and men raced and toured on dusty and bumpy terrain. Helmets also weren't part of the equation. If you were on a high-wheel bicycle and hit a rock, you'd go tumbling over the handlebars and onto your head. To reduce accidents and injuries, inventors modified the high-wheel bicycle. By the 1890s, the diamond-shaped frame with equal-sized wheels that we recognize today was standard, along with air-filled tube tires and gears. Innovations for the "safety bicycle" allowed riders to gain speed with a lower chance of peril—turning up the volume on the bicycle fad while also changing the game for women."

I mentioned the safety bicycle a bit earlier, and looking at the early ones, they're quite a bit like ours today.

The bicycle "extended women's mobility outside the home. A woman didn't need a horse to come and go as she pleased, whether to work outside the home or participate in social causes. Those who had been confined by Victorian standards for behavior and attire could break conventions and get out of the house.

Like most tech when it's new, only well-to-do Americans could afford a bicycle at first. In the 1890s, new bikes could cost $25-50 ($800-1600 in today's money). But women could bike because the safety bicycle's dropped frame allowed room for women's skirts. But who wants to ride a bicycle in a long skirt?

"The bicycle craze boosted the "rational clothing" movement, which encouraged women to do away with long, cumbersome skirts and bulky undergarments. Safety bicycle frames accommodated skirts, which got shorter, and the most daring women chose bloomers that resembled men's pants. A sport corset was designed with elastic for comfort during exercise."

And pretty soon, everyone was talking about cycling.

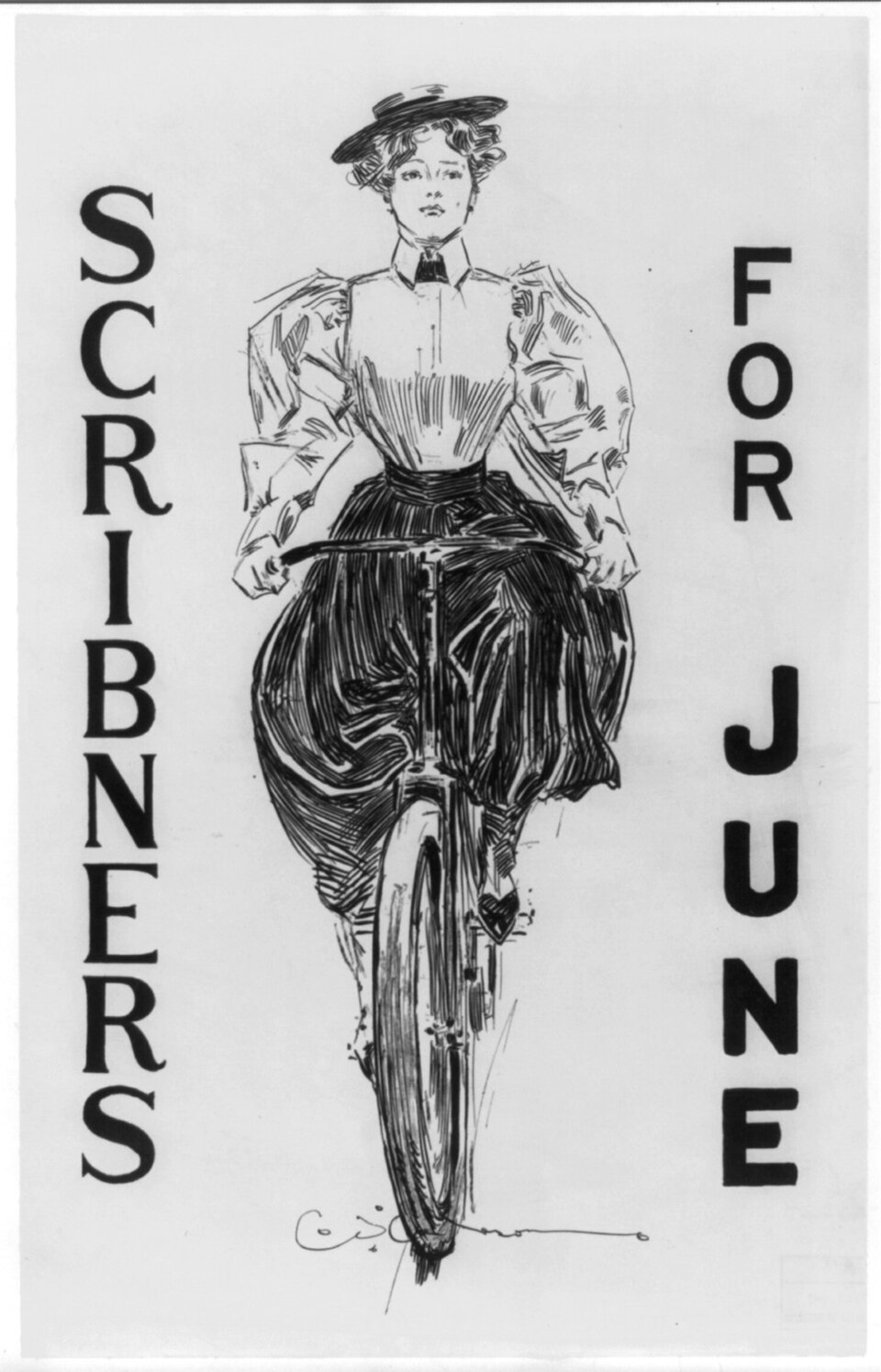

"Public discussions of cycling revolved around the "New Woman," invariably depicted as young, white, and attractive. Illustrator Charles Dana Gibson popularized the image of the turn-of-the-century's liberated woman with his drawings of the "Gibson Girl," who eagerly engaged in sports. Popular publications reinforced the association between women and cycling. 'The typical girl of the present period is the bicycle girl,' announced Ladies' World in 1896. That same year, Bicycling for Ladies offered both practical and fashionable tips for female cyclists."

And of course, everyone has an opinion about cycling.

"Suffragist Susan B. Anthony proclaimed that the bicycle has 'done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.' More cautiously, gynecologist Robert L. Dickinson warned against the sensual possibilities of cycling. While feminists and physicians debated the benefits of the bicycle, the diaries and photographs of one quintessential "New Woman," May Bragdon, provide greater insight into how this social trend affected daily life.

In the mid-1890s, May and her friends—all middle-class, white, single professionals in their twenties and thirties—went "bicycle-crazy." They eagerly purchased and compared bicycles, wholeheartedly adopted new fashions adapted to cycling, and enthusiastically supported new spectator sports featuring bicycles, such as races and expositions. But most of all, they thoroughly enjoyed the new freedoms offered by bicycles, which granted them increased mobility, offered new opportunities for outdoor recreation, and led to more spontaneous socializing in both mixed-gender and same-sex groups."

May originally was riding bicycles in "an old shirt waist & skirt", but eventually she and her friends started wearing shorter skirts and their male counterparts were wearing knickers. Some women went even further outside the fashion norms by wearing bloomers or split skirts. Women started filing patents for new ways to keep skirts out of the pedals, new corsets to keep upright but not be painful, etc.

But the cultural aspect of bicycling at this time steadily grew into an uproar. "From the outset, the renegade New Woman openly defying the conventions of Victorian womanhood was the subject of attacks from the male bourgeois establishment and a ridiculing campaign in the periodical press. In the public discourse she was accredited with often contradictory features that place her in opposition to the widely admired angel in the house. Averse to the institution of marriage and maternity, sexually licentious, decadent, mannish, asexual, and maculinised by education, career ambitions and unfeminine clothing, the New Woman was perceived as a threat to the social fabric of Victorian society. Vocal in her claim to enjoy educational, employment and political rights equal to those of men, the New Women was perceived as a continuator of Mary Wollstonecraft's early feminist agenda and its later espousal by John Stuard Mill.

And this is where we hear the awful, pretty ludicrous phrase, "bicycle face".

"...sexual polarisation became entrenched, and arguments asserting women's mental and physical incapacity to perform 'manly' activities were used as a defensive response to the ongoing change in women's status, which was threatening to subvert established social roles and norms…the adoption of the bicycle by women caused a strong reaction from the conservative Victorian establishment. Their critical opinion…[was] supported with religious, moral, medical, and scientific arguments, penetrated public discourse on women's bicycling and was reflected in the tone of the coverage it received in the press."

– From "Female Cycling and the Discourse of Moral Panic in Late Victorian Britain" by Beata Kiersnowska for the Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies, December 2019

According to The Literary Digest, Sept. 7, 1895 (p. 548).

"Warning against excessive indulgence in "wheeling" will perhaps be heeded more on account of the discovery of the alleged "bicycle face" by English medical papers. It is claimed that over-exertion, the upright position on the wheel and the unconscious effort to maintain one's balance tend to produce the "bicycle face."

"…talk about the "bicycle face" has gained considerable currency and given rise to grave discussion concerning the causes and remedies of the phenomenon."

Doctors were suddenly VERY worried about bicycling and uterine health (because women's stock was tied directly to their ability to reproduce). And it wasn't only male doctors. Arabella Kenealy, a British writer, physician, anti-feminist, and eugenicist wrote extensively on her views, and the freedom around which bicycles gave women was just another concern for her. She believed all exercise impacted a woman's ability to have children.

Physician and author Arthur Shadwell claimed to have coined the term "bicycle face" in The National Review:

"Some time ago I drew attention to the peculiar strained, set look so often associated with this pastime and called it the "bicycle face.' The general adoption of the phrase since then indicates a general recognition of its justice. Some wear the "face" more and some less marked, but nearly all have it, except the small boys… Has anybody ever seen persons on bicycles talking and laughing and looking jolly, like persons engaged in any other amusement? Never, I swear."

Shadwell was often quoted in the press, and he really liked to expound upon all the dangers of bicycling for women, including but not limited to: "exhaustion, nervousness, anxiety, goiter conditions, internal inflammation, chronic dysentery and infertility." He also talked about skeletal deformities and curvature of the spine, which would give women a "mannish" walk and ruddy complexion.

None of this stopped women from cycling. In fact, this concern only helped boost feminist views and talk around more freedom and rights for women. One day you can bike, the next day maybe you can vote.

And of course, it wouldn't be a social and moral panic without trying to question a woman's suitability for parenting/motherhood.

"Women were warned that cycling while pregnant would lead to foetal deformities, difficult labour, stillbirths and an inability to breastfeed, not to mention indicating that they were poor material for motherhood by exposing their unborn children to harm or death due to cycling accidents. In a sensational 1899 article entitled "Woman as an athlete" published in Nineteenth Century, Dr Arabella Kenealy projected that at its most extreme, by impeding reproduction and distracting women from motherhood for the pursuit of pleasure, cycling could lead to race suicide amongst middle class British and North American people of child bearing age who practiced it."

"Satirical magazines such as Punch regularly ran comic illustrations showing lady cyclists mistaken for men, such as a vicar asking rational riders to remove their hats before entering a church in the manner of gentlemen, or acting as men such as the lady cyclists proposing to her emasculated suitor in the sketch shown right. An 1897 example from the CTC Gazette shown at the close of this post depicts a street urchin approaching a woman in cycling garb who he presumes to be a man, offering a box of matches and addressing her as 'My Lord.'"

"Munsey's Magazine said it best in 1896: 'To men, the bicycle in the beginning was merely a new toy, another machine added to the long list of devices they knew in their work and play. To women, it was a steed upon which they rode into a new world.'

People who rode hard and fast (particularly women) were called Scorchers. "The Feminine Scorcher" published in The Saturday Evening Mail of Vigo County, Indiana on May 9, 1896 (reprinted from Godey's Magazine) said it all.

And once a woman became a scorcher, there was no telling what she'd do next. Wearing skimpier garments? Bloomers? The bicycle seat would surely lead to looser morals!

But bicycle face was the thing that really caught the media's attention, and it affected men as well as women. And a few even took it further, to something they coined "cyclemania".

"Cyclomania was defined as a chronic psychosis with symptoms similar to hysteria or kleptomania that afflicted women. Cyclomaniacs were described as being overwhelmed by an unnatural passion for cycling. They rode too often, too far, too fast and to a point of exhaustion. Victims of the disease were unilaterally obsessed with cycling. Wheelwoman described the condition as a compulsive disorder that compelled otherwise rational women to tackle every hill and left them with an insatiable appetite for speed. It was likened to an intoxication and addiction that left women dishevelled, shamed, lacking self-control, likely to engage in risky behaviour and generally behaving in an un-ladylike fashion not dissimilar to the chronically drunk woman. Maria Ward, author of the 1896 guidebook Bicycling for Ladies warned that "scorching is a form of bicycle intoxication," which once a taste for it was acquired, the body came to crave at exception of all else. It should come as no surprise that one of the signs that a woman had developed cyclomania was that she put cycling ahead of her family–a sure sign of an unhealthy infatuation in the Victorian mind."

It was disease-mongering and moral panic at its finest. We see moral panics pop up at times of great social change - you only need to look at the Satanic Panic of the 1980s. That was largely based around the fears of women going into the workplace in mass droves, leaving their children in the care of strangers at daycares and other houses. (This particular panic has been covered many times by many podcasts, so we won't go into it here.)

And what's really going on here is a discourse on women's bodies, the medicalization of them, and gender and social politics

And then New York World published a ridiculous list of "don'ts" for bicyclists, most of which were clearly aimed at women.

- Don't be a fright.

- Don't faint on the road.

- Don't wear a man's cap.

- Don't wear tight garters.

- Don't forget your toolbag

- Don't attempt a "century."

- Don't coast. It is dangerous.

- Don't boast of your long rides.

- Don't criticize people's "legs."

- Don't wear loud hued leggings.

- Don't cultivate a "bicycle face."

- Don't refuse assistance up a hill.

- Don't wear clothes that don't fit.

- Don't neglect a "light's out" cry.

- Don't wear jewelry while on a tour.

- Don't race. Leave that to the scorchers.

- Don't wear laced boots. They are tiresome.

- Don't imagine everybody is looking at you.

- Don't go to church in your bicycle costume.

- Don't wear a garden party hat with bloomers.

- Don't contest the right of way with cable cars.

- Don't chew gum. Exercise your jaws in private.

- Don't wear white kid gloves. Silk is the thing.

- Don't ask, "What do you think of my bloomers?"

- Don't use bicycle slang. Leave that to the boys.

- Don't go out after dark without a male escort.

- Don't without a needle, thread and thimble.

- Don't try to have every article of your attire "match."

- Don't let your golden hair be hanging down your back.

- Don't allow dear little Fido to accompany you

- Don't scratch a match on the seat of your bloomers.

- Don't discuss bloomers with every man you know.

- Don't appear in public until you have learned to ride well.

- Don't overdo things. Let cycling be a recreation, not a labor.

- Don't ignore the laws of the road because you are a woman.

- Don't try to ride in your brother's clothes "to see how it feels."

- Don't scream if you meet a cow. If she sees you first, she will run.

- Don't cultivate everything that is up to date because you ride a wheel.

- Don't emulate your brother's attitude if he rides parallel with the ground.

- Don't undertake a long ride if you are not confident of performing it easily.

- Don't appear to be up on "records" and "record smashing." That is sporty.

Full Source List

- https://www.vox.com/2014/7/8/5880931/the-19th-century-health-scare-that-told-women-to-worry-about-bicycle

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bicycling_and_feminism

- https://www.europeana.eu/en/stories/women-beware-of-bicycle-face

- https://www.sheilahanlon.com/?p=1990

- https://www.entandaudiologynews.com/features/history-of-ent/post/beware-of-bicycle-face

- https://racingnelliebly.com/strange_times/doctors-triggered-victorian-bicycle-face/

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Justin-Spinney/publication/235357395_Cycling_the_City_Non-Place_and_the_Sensory_Construction_of_Meaning_in_a_Mobile_Practice/links/5579505808ae75363755c2ae/Cycling-the-City-Non-Place-and-the-Sensory-Construction-of-Meaning-in-a-Mobile-Practice.pdf#page=170

- https://www.atlantisjournal.org/index.php/atlantis/article/view/598/299

- https://commonplace.online/article/how-bicycles-liberated-women-in-victorian-america/

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/2018/apr/16/the-ingenious-cyclewear-victorian-women-invented-to-navigate-social-mores

- https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/women-victorian-era-society-bike-riding

- https://www.si.edu/stories/19th-century-bicycle-craze

- https://www.atlantisjournal.org/index.php/atlantis/article/view/598

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/2015/jun/09/feminism-escape-widneing-gene-pools-secret-history-of-19th-century-cyclists

- https://www.gold.ac.uk/news/bikes-and-bloomers/

- https://blog.nls.uk/cine-cycles-women-bicycles-and-a-sense-of-freedom/

- https://victorianist.wordpress.com/2015/04/13/chains-of-freedom-the-bicycles-impact-on-1890s-britain/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penny-farthing

- https://guides.loc.gov/bicycles-cycling-history/subject/women

- https://blog.library.si.edu/blog/2020/05/26/breaking-the-cycle-the-kittie-knox-story/#.YfwryvXMIwT

- https://books.google.com/books?id=Eqk5AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA548#v=onepage&q&f=false

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Velocipede#Boneshaker

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arabella_Kenealy

![Julia Obear, messenger girl at the National Women's [i.e. Woman's] Party headquarters](https://061c91ca8a.clvaw-cdnwnd.com/97c147cac6658850153a8027db00ef8a/200006084-56ac256ac4/Julia_Obear%2C_messenger_girl_at_the_National_Women-s_%28i.e._Woman-s%29_Party_headquarters_LCCN92522519_%28cropped%29.jpeg?ph=061c91ca8a)