Anatomical Vensuses

In some ways, this is a short version of the history of wax. An incredibly malleable material that doesn't degrade the way other organic compounds do, wax can make molds, absorb paint, and be made into incredibly accurate, often eerily exact replicas of bones, tissue, and whole people (like in Madame Tussaud's famous wax celebrity museums).

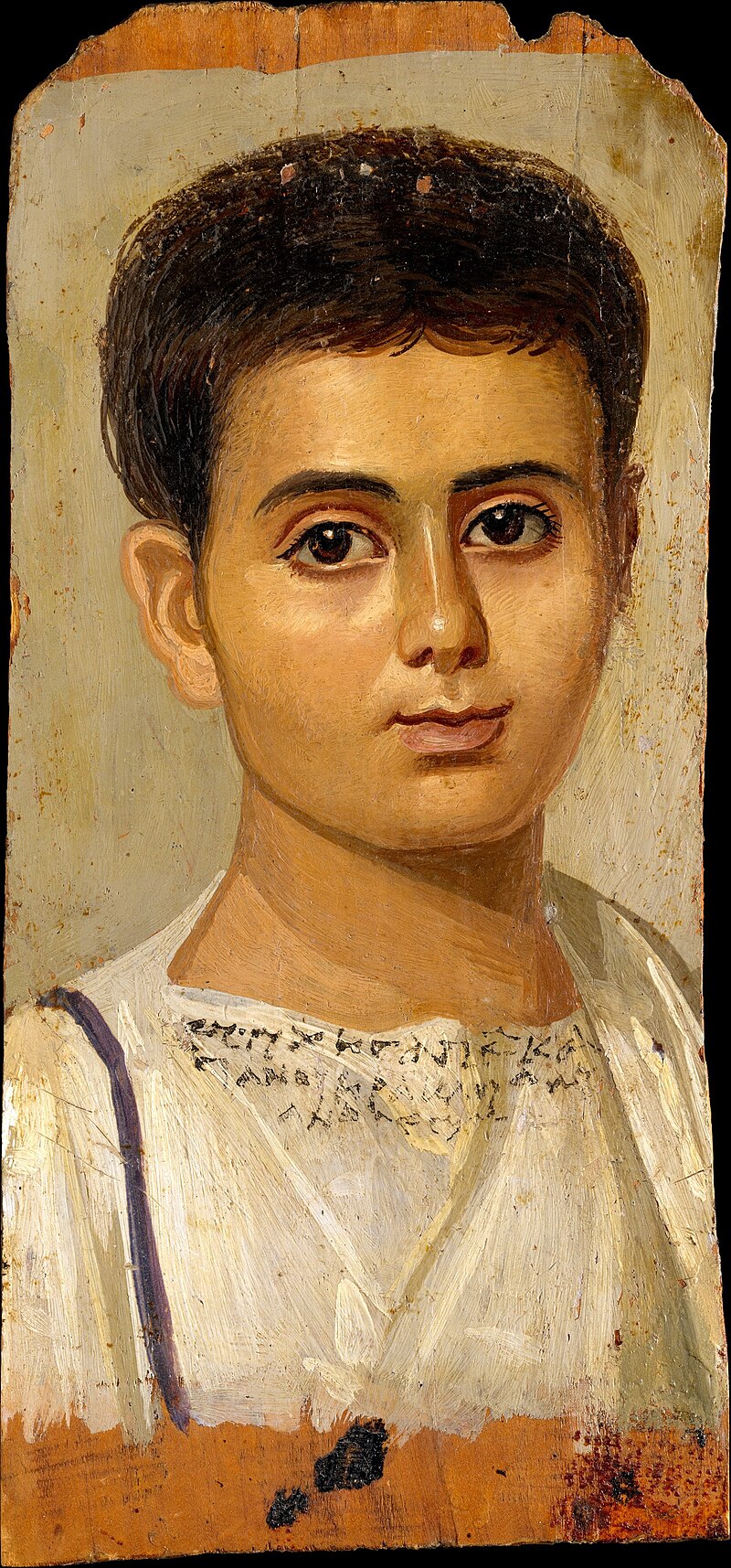

Wax has been used "since ancient times by the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans and continues to be an important material today". We make wax out of animal byproducts like beeswax and lanolin, from plants, and from minerals. The earliest surviving wax art pieces are the Fayum mummy portraits, where the "portraits covered the faces of bodies that were mummified for burial…(one technique was made of) encaustic wax", otherwise known as hot wax painting. The wax is heated, colored pigments are added, and the hot wax is applied to a surface like wood or canvas, and as the wax cools, tools are used to carve out the excess so only the wax adheres to the face or body part. It makes for eerily accurate paintings. There are about 900 of these mummy portraits still in existence, with the majority having been found in the necropolis of Faiyum.

Episode: File 0154: Anatomical Lightning of Quebec

Release Date: Sept 5 2025

Researched and presented by Halli

It's one thing to preserve someone's likeness - it's done in memoriam for a loved one who has passed. Considering what we know about the death rites and rituals of the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, these wax mummy portraits are oddly endearing. And if we move far ahead in time to the Middle Ages and Victorian eras, we see death and the body treated rather differently, especially where Christianity enters the mix. Grave robbing became a lucrative, but dangerous, way of getting bodies to medical professionals for study and dissections - but of course the bodies were almost always of the poor and criminal classes. The Victorians in particular harbored a distinctly morbid fascination with death and dying; "Death was an acknowledged and public event, and responses to death were at the forefront of the social customs of the time". Mourning portraits and death masks were common, and funerals were often held in the home. Of remarkable note was Queen Victoria's mourning of her husband, Prince Albert. She mourned for 40 years, "dressing in black every day and keeping their home exactly as it was the day he died". Death was a "common domestic fact of life for Victorians…so they developed elaborate rituals to deal with it"

And swirling amidst all of this death fascination was also the fixation on the morbid - the body as a vessel, as a sinful thing to be hidden, but also as a means to understand their hard, cruel world.

The Body as Vessel, Object of Fascination, and Source of Sin

"The achievement of having originated the creation of anatomical models in coloured wax must be ascribed to a joint effort undertaken by the Sicilian wax modeller Gaetano Giulio Zumbo and the French surgeon Guillaume Desnoues in the late 17th century. Interest in anatomical wax models spread throughout Europe during the 18th century, first in Bologna with Ercole Lelli, Giovanni Manzolini and Anna Morandi, and then in Florence with Felice Fontana and Clemente Susini."

–"Anatomical models and wax Venuses: art masterpieces or scientific craft works?" by R Ballestriero, 2009

Wax has a special place in many cultures. From art and religion to magic rituals and funerals, wax is now what we think of when it comes to candles. But wax was a great material from which to make art and study science for many centuries.

"The most important characteristic of wax for artistic purposes is its capacity to afford a remarkable mimetic likeness far surpassing that given by any other material. It is flexible, easy to work, can be coloured, and can be adorned using organic materials such as body hair, hair, teeth and nails….From an artistic point of view it virtually disappeared in the 19th century, surviving only in a minor way for votive uses (for example for the creation of ex voto objects and statues, at times containing relics, of saints and martyrs) and in secular waxworks such as those displayed at Madame Tussaud's Museum in London. In contrast, the use of wax modelling techniques for didactic and scientific purposes increased considerably for the study of normal and pathological anatomy, obstetrics, zoology and botany."

The Renaissance of the 16th century prompted new scientific interest in anatomy, which led to physicians wanting to study cadavers, but many religious beliefs got in the way of procuring dead bodies through any means save for those executed for crimes. So the physicians turned to wax. Italy led the way in this peculiar meshing of art and science, then spread to France and England, largely thanks to the work of G.G. Zumbo, an abbot who initially undertook works of a religious nature, but eventually became fascinated with death and disease. "He produced four highly realistic compositions known as 'Theatres of Death', which convey a general sense of decay and the precariousness of life…In the works produced by Zumbo, both his tableaux and anatomical heads (Fig. 1), the sense of the macabre is invariably explicitly conveyed. His compositions clearly reveal Zumbo's interest in death and disease. These tableaux, still on display at La Specola Museum, Florence, portray destruction in minute detail and with a morbid attention to trivial aspects; death is illustrated as an event that suffocates and eliminates any vestige of beauty."

Zumbo's craft and skill were widely renowned in the late 1600s, and he eventually moved to Paris where, supported by Louis XIV's court, he worked with other physicians and men of science to create more anatomical waxes until his death in 1701. These waxes were incredibly accurate in anatomical detail but also showing the first stages of decomposition. And thanks to this one man, the art of wax anatomical modeling evolved and spread through Western Europe.

I mentioned the La Specola Museum in Florence, Italy, and it's worth taking a little detour to talk about this incredible - and very creepy - place. Founded by Grand Duke Peter Leopold in 1775, the institution's most renowned work was a "reclining female figure whose torso opens to reveal seven anatomical layers of internal organs and a tiny gestating fetus". She is the original Anatomical Venus, and she is both mesmerizing and intensely disturbing.

La Specola itself is a fascinating place, with a history that ties back to the Medici Family and is the oldest scientific Museum of Europe. The museum today spans 34 rooms and contains the most eclectic collection of items, from a stuffed hippopotamus (a pet of the Medici Family in the 17th century) to the anatomical waxes we're talking about, and much more. It is the original Bodyworks display, except no real bodies lie in glass cases. Every single "body" or "body part" is made of wax and done in exquisite detail.

Slideshow can be found hereAnatomical Venus

I cannot recommend more highly Joanna Ebenstein's 2016 book The Anatomical Venus, which is still available for sale. I bought a copy myself and it is the singular work that dives into the history of these figures and how anatomical studies developed over the centuries. What I'm talking about today is an overview; Ebenstein's book, along with the other sources cited here, are all great sources to look into if you want more gritty details.

"These 'curious afterlives,' as Ebenstein terms them, extend from Enlightenment Florence and early modern anatomical illustration to fairground spectacle, erotic fetish, and the surrealist grotesque."

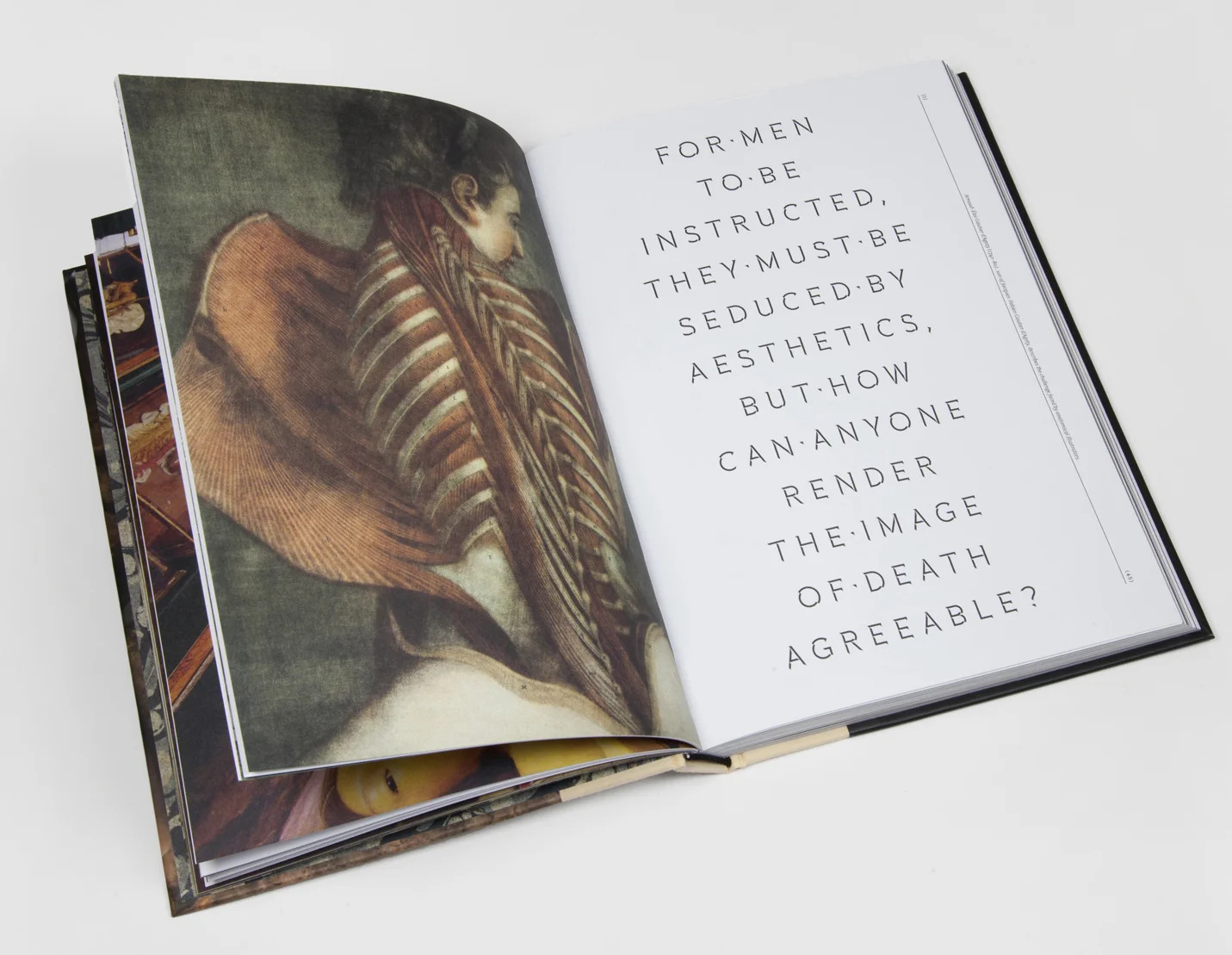

But the anatomical Venus was also incredibly groundbreaking at the time, to the point that some of the body parts and pieces modeled in wax had no name yet. She was both a teaching tool and also an idealized human form, which critics wrote off as no more than sideshow or peepshow spectacle. They called it grotesque or ungodly. Scientists called it remarkable, an achievement.

Under his director, Felice Fontana, Susini and wax modelers under his tutelage made more than 2,500 pieces, from singular body parts to entire women (and occasionally a man); of those, about 1,400 pieces can still be found at La Specola. Eighteen of those are life-sized figures, but only the Anatomical Venus can be taken apart. Today, these life-sized wax women are also known as Slashed Beauties or Dissected Graces; at least with the name Anatomical Venus, she seems to have a purpose and not simply to be goggled at.

The Anatomical Venuses were made at a time when science and religion, art and anatomy, were complementary rather than contradictory. "In 1742, Pope Benedict XIV –better known as the "Enlightenment Pope"--founded the world's first wax anatomical museum in Bologna", a precursor to La Specola. This pope was dedicated to enmeshing scientific and ecclesiastical practices, to the point where "he required alleged miracles to be confirmed using scientific methodology". He even went so far as to ask his flock to donate their kin, "dead by whatever means," for dissection and study.

And many anatomists and physicians at the time saw their practice and study as an expression of religious devotion. As Ebenstein writes in her book, "the Anatomical Venus was created at a moment in which 'the human being…was understood to be the pinnacle of God's creation and a microcosm of the universe; to know the human body was, in a sense, to know the world and the mind of God."

When I learned about her existence some months ago, I found myself straddling the valleys of fascination and repulsion. It is admittedly hard to see these figures through a modern lens without noting that they were made female for many reasons, and that some of those reasons are rooted in the idea that women were both objects of fetish and fascination, and at the same time considered helpless or stupid. Add in the fact that female physicians were incredibly rare at the time; the first female physician in Europe, a German woman named Dorthea Erxleben, received her degree in 1754. But they were very few and far between.

So where does that leave us with these Slashed Beauties? The Anatomical Venus, as eerie and stomach-churning as it may be, gives us a deep insight into a time when religion and science were deemed one and the same. Today that divide is a chasm and we are constantly putting down one to raise up the other. It makes me wonder if such a balance could ever be found again, and if it could, would it be doomed?